title, author, geometry, output

| title | author | geometry | output | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Análise Numérica - Trabalho Prático 3 |

|

margin=2cm | pdf_document |

Motivação

Pretende-se interpolar uma função através do método de Newton em diferenças divididas, construir o spline cúbico natural e proceder a uma comparação e interpretação dos resultados obtidos.

1.a)

using points_t = std::pair<std::vector<double>, std::vector<double>>;

using matrix_t = std::vector<std::vector<double>>;

std::vector<double> newton_differences(points_t points) {

std::vector<double> factors{};

auto &[x, fx] = points;

int n = points.first.size();

for (int i = 1; i <= n; ++i) {

factors.push_back(fx[0]);

for (int j = 0; j < (n - i); ++j) {

fx[j] = (fx[j + 1] - fx[j]) / (x[j + i] - x[j]);

}

}

return factors;

}

double newton_polynomial(points_t points, std::vector<double> factors, double x) {

auto xs = points.first;

int n = points.second.size() - 1;

double val = 0;

for (int k = 0; k <= n; ++k) {

double acc = 1;

for(int i = 0; i < k; ++i) {

acc *= (x - xs[i]);

}

val += acc * factors[k];

}

return val;

}

\pagebreak

void exercise_a(points_t points) {

auto &[xs, fx] = points;

auto factors = newton_differences(points);

std::ofstream poly{"a_polynomial.txt"};

for(double x = 0; x < 4; x += 0.001)

poly << x << " " << newton_polynomial(points, factors, x) << '\n';

std::ofstream spline{"a_spline.txt"};

unsigned long n = xs.size();

matrix_t mat(n, std::vector<double>(n + 1));

calculate_natural_cubic_spline_matrix(points, mat);

for(double x = 0; x < 4; x += 0.001)

spline << x << " " << natural_cubic_spline(points, mat, x) << '\n';

}

1.b)

void calculate_natural_cubic_spline_matrix(points_t points, matrix_t &mat) {

auto &[xs, fx] = points;

int n = xs.size();

// Construção da matriz

for (int i = 1; i < n - 1; ++i) {

mat[i][i - 1] = (xs[i] - xs[i - 1])/6;

mat[i][i] = (xs[i + 1] - xs[i - 1])/3;

mat[i][i + 1] = (xs[i + 1] - xs[i])/6;

mat[i][n] = (fx[i + 1] - fx[i])/(xs[i + 1] - xs[i]) -

(fx[i] - fx[i - 1])/(xs[i] - xs[i - 1]);

}

mat[0][0] = 1;

mat[0][n - 1] = 0;

mat[n - 1][n - 1] = 1;

mat[n - 1][n] = 0;

// Passar para a forma triangular

for (int k = 0; k < n; ++k) {

for (int i = k + 1; i < n; ++i) {

if (mat[k][k] != 0) {

double mul = mat[i][k]/mat[k][k];

for (int j = k; j < n; ++j) {

mat[i][j] -= mul * mat[k][j];

}

mat[i][n] -= mul * mat[k][n];

}

}

}

\pagebreak

// Resolução da matriz

for (int i = n - 1; i > 0; --i) {

if (mat[i][i] != 0) {

double mul = mat[i - 1][i]/mat[i][i];

for (int j = 0; j < n + 1; ++j) {

mat[i - 1][j] -= mul * mat[i][j];

}

mat[i][n] /= mat[i][i];

mat[i][i] = 1;

}

}

}

double natural_cubic_spline(points_t points, matrix_t &mat, double x) {

auto &[xs, fx] = points;

int n = xs.size();

int i = 0;

for (int i_ = 0; i_ < n; ++i_) {

if (xs[i_] > x){

i = i_;

break;

}

}

double hi = xs[i] - xs[i - 1];

return mat[i - 1][n] * std::pow((xs[i] - x), 3)/(6 * hi) +

mat[i][n] * std::pow((x - xs[i - 1]), 3)/(6 * hi) +

(fx[i - 1] - mat[i - 1][n] * (hi * hi)/6)*(xs[i] - x)/hi +

(fx[i] - mat[i][n] * (hi * hi)/6)*(x - xs[i - 1])/hi;

}

void exercise_b() {

points_t points;

auto &[xs, fx] = points;

auto f = [](double x) { return 4 * std::pow(x, 2) + std::sin(9 * x); };

for (double x = -1; x <= 1; x += (1 - -1)/8.0) {

xs.push_back(x);

fx.push_back(f(x));

}

std::ofstream poly{"b_polynomial.txt"};

auto factors = newton_differences(points);

for(double x = -1; x < 1; x += 0.001)

poly << x << " " << newton_polynomial(points, factors, x) << '\n';

std::ofstream spline{"b_spline.txt"};

unsigned long n = xs.size();

matrix_t mat(n, std::vector<double>(n + 1));

calculate_natural_cubic_spline_matrix(points, mat);

for(double x = -1; x < 1; x += 0.001)

spline << x << " " << natural_cubic_spline(points, mat, x) << '\n';

}

2.a)

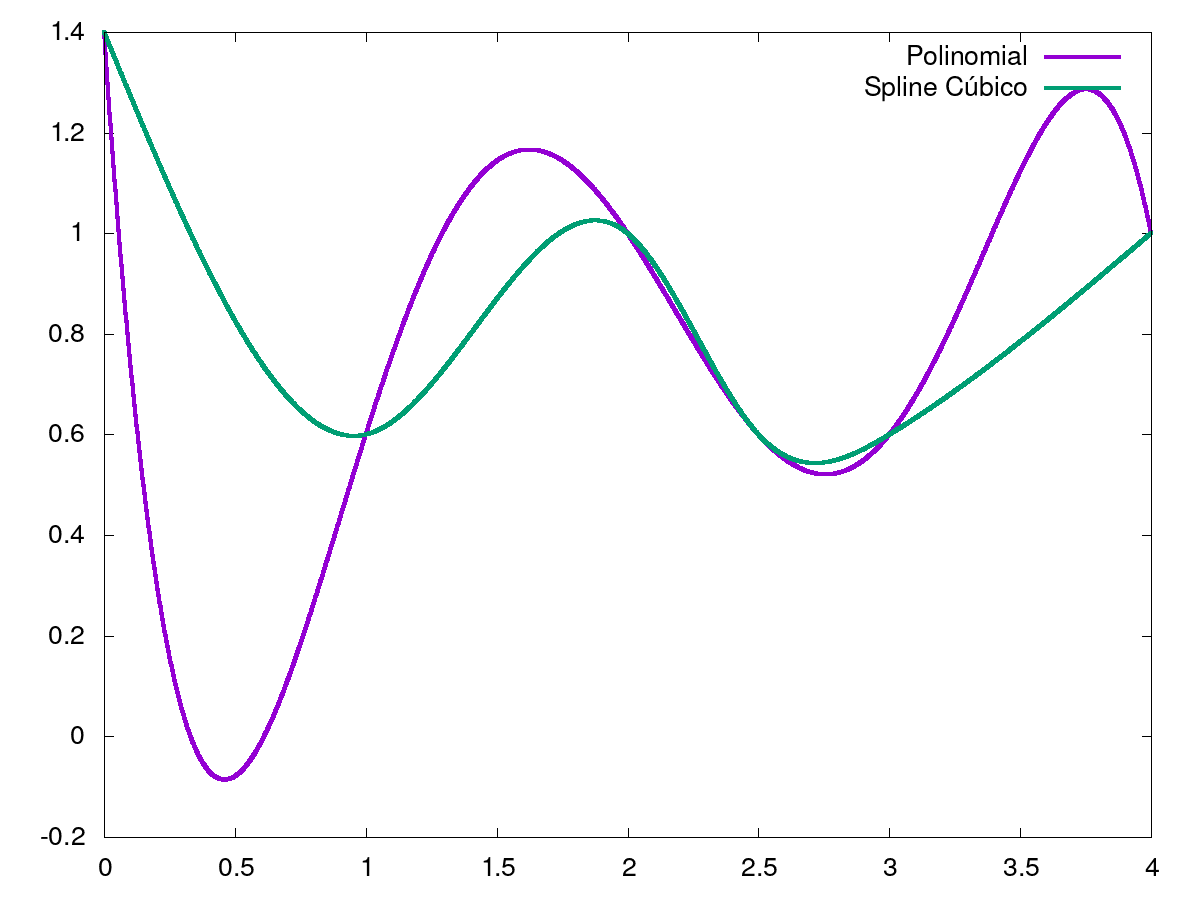

Através dos graficos é possivel verificar que os valores das funções coincidem no pontos de interpolação, como era esperado. Não é possivel determinal qual a melhor aproximação sem conhecer a função original. O programa foi modificado para imprimir a matriz inicial assim como o resultado final, que foi utilizado para calcular o vetor resíduo e a norma deste. Este script encontra-se em baixo.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import numpy as np

from scipy.linalg import solve

from numpy.linalg import norm

# Matriz construída pelo programa em C++

A = np.matrix([[1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0.166667, 0.666667, 0.166667, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0.166667, 0.5, 0.0833333, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0.0833333, 0.333333, 0.0833333, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0.0833333, 0.5, 0.166667],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1]])

b = np.array([0, 1.2, -1.2, 0.8, 0.4, 0])

x2 = np.array([0, 2.76846, -3.87386, 3.30622, 0.248963, 0])

x = solve(A, b)

print(norm(x - x2))

Obteu-se para a norma do vetor resíduo o valor 1.0e-05 que

é considerado aceitável visto que os dados são apresentados

com dois algarismos significativos.

\pagebreak

2.b)

i)

\begin{array}{c|ccccccccc}{x_{i}} & {-1} & {-0.75} & {-0.5} & {-0.25} & {0} &

{0.25} & {0.5} & {0.75} & {1} \\ \hline {f_{i}} & {3.58788} & {1.79996} &

{1.97753} & {-0.528073} & {0} & {1.02807} & {0.0224699} & {2.70004} & {4.41212}

\end{array}

ii)

De forma análoga ao exercício 2.a) foi calculada a norma do vetor resíduo usando o seguinte script:

A = np.matrix(

[[1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0.0416667, 0.166667, 0.0416667, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0.0416667, 0.166667, 0.0416667, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0.0416667, 0.166667, 0.0416667, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0.0416667, 0.166667, 0.0416667, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0.0416667, 0.166667, 0.0416667, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0.0416667, 0.166667, 0.0416667, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0.0416667, 0.166667, 0.0416667],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1]])

b = np.array([0, 7.862, -10.7327, 12.1347, 2, -8.13471, 14.7327, -3.862, 0])

x2 = np.array([0, 73.9996, -107.31, 97.6564, 7.91753, -81.3265, 122.156, -53.7109, 0])

x = solve(A, b)

print(norm(x - x2))

Obteu-se para a norma do vetor resíduo o valor 9.0e-04 que

é considerado aceitável visto que este valor tem uma magnitude pequena.

\pagebreak

iii)

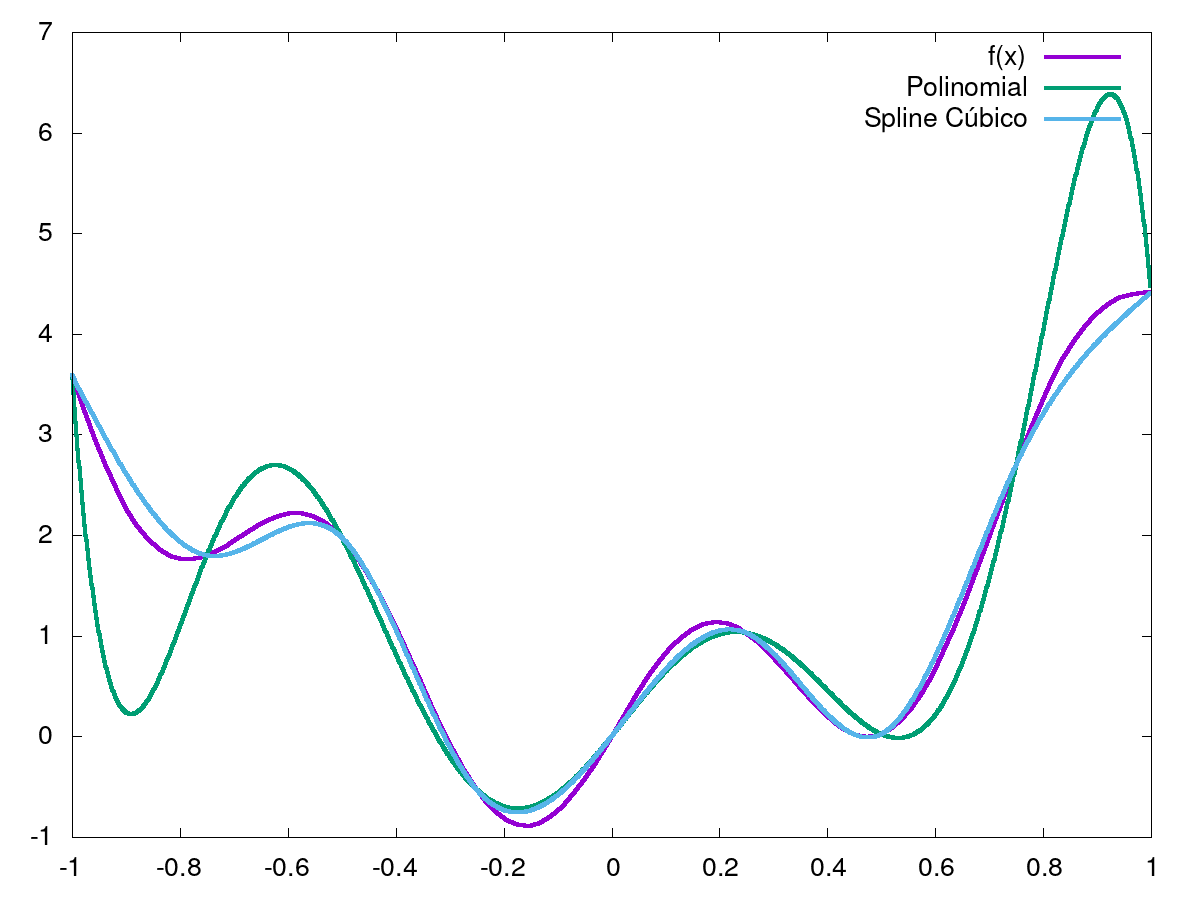

| x | f(x) | p(x) | abs(f(x)-p(x)) | s(x) | f(x)-s(x) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.30 | 0.78737988 | 0.923318 | 1.4*10^{-1} |

0.826621 | 4.0*10^{-2} |

| 0.83 | 3.68278040 | 4.834190 | 1.2 | 2.4*10^{-1} |

2.4*10^{-1} |

Verificamos que o erro do spline cubico é inferior em ambos os casos. Além disso em ambos os casos o erro é maior quando a abcissa é mais distante do centro do intervalo.

iv)

É possivel observar que a interpolação pelo spline aproxima, em geral, melhor a função dada do que o polinomio. Em particular verifica-se que o erro do polinomio acentua-se à medida que as abcissas se afastam do centro do intervalo de interpolação.